Narrative 1

During the Visual Narrative Project, we were challenged to respond to the question “How well can you visually tell a structured story?” We commenced the unit with an exploration of prose fiction and graphic novel, in which we furthered our descriptive story-telling skills by learning about communicating character and story arc, narrative digital art, and storyboards. We also deepened our technical communication skills by learning a variety of modern professional equipment and applications such as Wacom Digital Drawing Pads, lighting equipment, downshooters, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Animate, Adobe Premiere Pro, Avid Pro Tools, HTML/CSS, and Google Apps.

Story

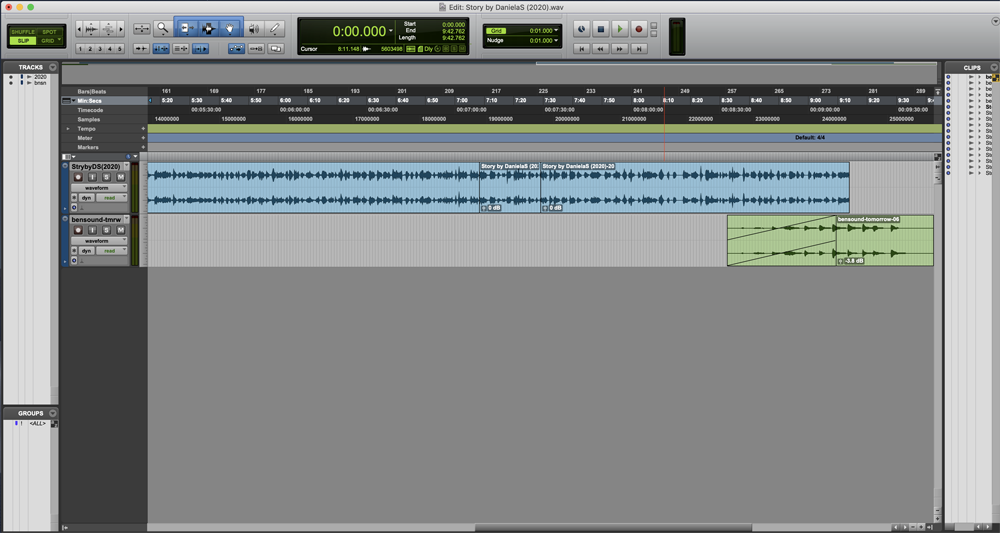

For our narrative English Project, we created a short story on the topic of our choice, focusing on the narration of emotion and precise detail. I decided to write my story about a Guatemalan mother immigrating to the United States with her two children as an attempt to increase awareness and humanization of immigrants seeking refuge in the United States. I then recorded this story using a portable recorder and edited out mistakes and added music on Pro Tools. Through this project, I learned how to communicate emotion without plainly describing it, and it allowed me to incorporate my personal beliefs into my work.

“One Last ‘I Love You'”

It was the sirens. The loud, excruciating sirens. Squeaky with danger and glaring with fear, pulsing from every direction. It seemed like they would never stop. And they didn’t. To this day, I find myself awake drenched in a cold sweat, my long black hair dripping cold, with those sirens blaring at the touch of my ears. I scream for them to stop, to leave me alone, to bring me my children back. But the thing about the universe is that it doesn’t obey any commands. It doesn’t care what you’ve been through or what has happened. It sneaks smoothly beneath your worst fears and poisons your body when you’re at your weakest.

I will never forget the last day I saw my babies: Jose and Adriana, my sweet pair of angels. It was August 23rd, 2017. A dry, scorching hot desert sun surrounded us, sweltering our bodies and minds. At the time, he was ten and she was seven, far too young to understand why we had to leave Guatemala, but too old to be completely blinded by innocence.

We arose early in the morning to complete the last leg of our trip: crossing the Mexican border into the United States (about a 12 kilometer traverse). At the time, we were staying in a creaky white chicken imports truck that smelled like fear and rotting poultry. They had promised us that for $3,000 dollars, they would take us all the way from Guatemala into the United States. However, I harbored no hopes of acquiring that much money, and beneath stories of families who had been murdered or sold into human trafficking for their inability to pay these dues, we found ourselves dropped off in the outskirts of Tijuana for a mere $500. This meant another 12 kilometers into California.

I dreamed of exploring the golden poppy fields and bright blue Pacific cliffs like I had seen on TV, but I knew not to get my hopes up. These 12 kilometers were the most dangerous. I did not want to undermine the tremendous adversity we had already undergone in the earlier stages of our trip: we had been kept in a small confined airtight space with three other families for over a month. It was impossible to even stretch out to sleep. Deprived of daylight, two died on that trip due to improper sanitation and dehydration. Two human beings who had risked everything they had to traverse to the United States in search of a better life. Two human beings who were trying to provide for their families as best as they could. Two human beings who had saved money for years to afford this trip, but would instead end up as cadavers someplace off of the long, windy highways of Durango (Or perhaps Sinaloa. I was good at geography, yet the sickening ride had made me lose track of time and space). We had a fairly calm trip in comparison to many others. No gun-shots, no rapes, no violence inflicted upon us.

A couple of young men from two of the other families agreed to be used as drug mules for a night in exchange for a free passage. We met a man on a dirt road who handed them some packages and instructed them accordingly. We were told they would be back by 10 pm that evening. But it was 10, and then 11, and before we knew it, the sun was rising and and our trip continued as usual. We didn’t see them again, but we tried our best to pretend it never happened. I wanted to shield my children from the pain, so I made up a story that they had gone in a different truck so we would have more room.

By the time Adriana had woken up, on that last morning, the truck halted in the middle of an abandoned gas station. The station’s tall eggshell white walls rotted in rust, sending a slight sourness into the air. We were given directions on how to get past the border into The States, how to avoid border patrol, and lastly what to do in the case that patrol would find us. And just like that, the truck drove away into the unknown, leaving me and my children standing alone in the isolated desert-city, surrounded by nothing and everything.

We began marching forward, trying our best to keep our feet moving despite the blazing heat and our overworn shoes. To keep the time moving more quickly, we talked of what life would be like once we crossed the border. Adriana said the first thing she was going to do was learn how to ride a bike, something she always asked to do back in Guatemala, which I had to turn down because it was too dangerous for her to be on the streets and we couldn’t afford a bicycle. Jose said that he was going to learn how to play American Football, which he had been obsessing over for years, but had never actually been able to play because we lacked the equipment and a place for him to practice. I rambled on about how we would have a TV, perhaps even a car, how they would go to school, and how quiet the nights would be while we slept (the overridden gang-area we lived at in Guatemala was always loud with gunshots and threats, especially at night).

The shining sun hit my softly wrinkled face and my long dark braid bounced upon my back with every step. Hours passed and before we knew it, we could see the border: a grey brick fence probably around three meters high covered in graffiti containing all sorts of swear words, illustrations, and political messages. A crimson red, neatly written, stood out on its own: LA FRONTERAS, DONDE MUERE LA HUMANIDAD, or the borders, where humanity dies. I decided to brush it aside. As hope glimmered in our pupils, the three of us used the little energy we had left and ran towards the border. It was so close, I could feel the weight lifting off my shoulders. As we approached, I thought I heard a voice, but I looked around and no one was present, so we proceeded. We were one short climb away from freedom: my abusive husband, the poverty that affected us everyday, the gangs, the gunshots. Everything. We could leave it all behind, this was a fresh start.

The pulsing freshness swifted through my body, waking every nerve within me. I began climbing to the best of my ability. Despite being only 33, I had the knees and back condition of an old woman (probably because I worked with my dad in construction since I was about 7), but one more push, and I was there. So I pushed, and as I stood atop the wall, my insides burning with a sense of victory, I saw him. A blur of green and yellow writing with a gun even bigger than the ones the gang members carried back home. Behind him, sirens from approaching police cars screamed into the air. He yelled something I didn’t quite understand and pointed the gun at me. I screamed for my children to duck underneath the wall. I recalled what the truck driver had said- remain calm, obey commands, tell them you are seeking asylum. But this agent didn’t exactly look like the one that was helping people seek asylum. He was stern and had a grin of evil. He kept screaming, bringing the gun closer to me every second. At that point, a million thoughts and more rushed through my mind, yet one grew brighter than the rest: if my children don’t get across that border, they will never have a future. So, I did what I needed to do, and to this day it is the most painful decision that I have ever encountered. I instructed my children to climb across the wall, knowing they would not be shot because of their age. I told them to ask for a lawyer, and speak of the horrible conditions back home. Before I knew it, I was halfway back to the gas station fighting every urge in my body to turn around and go get my children, to say one last “I love you”. But I didn’t. I just kept running.

It’s been two years and I’ve yet to hear from them. The American system is nowhere near perfect, even I know that, but I can take comfort in knowing that I made a decision in which my children are safe, fed, educated, and healthy- all of which are things I couldn’t provide them with myself back in Guatemala. It’s heartbreaking to me that I had to do this. I’ve relocated in Baja California, working in a Mexican restaurant, and have begun my new life here, one far away from my husband. I hope that one day, my children will be able to come visit me. I will explain to them why I had to do this, how sorry I am, and how much I love them. As of now, I wipe my greasy fingers on my checkered red apron and continue to press down soft dough, longing for my children but carrying a sense of peace that they will go on to have better lives.

Behind The Scenes…

Short Story Author Study

Why Do We Always Say Nothing?

In The Thing Around Your Neck, Adichie Ngozi Chimamanda utilizes sensitive storytelling inspired from her own background to emphasize recurring themes in her novel, including the importance of resisting political oppression (“Cell One”), the struggle of immigrants’ assimilation into American culture (“Arrangers of Marriage”), and the roles that racism and sexism play in people’s lives (“Jumping Monkey Hill” and “Tomorrow is Too Far”). Through her work, Chimamanda accentuates the importance of maintaining one’s culture and individuality despite gender, racial, or cultural oppression. Through her beautifully complex storytelling, Chimamanda incorporates numerous literary devices to richen the significance of her work and better emanate her messages.

Political injustice and police brutality are prominent matters in today’s society, primarily in foreign countries where corruption and lack of regulation permit cruel forms of abuse to be enforced upon citizens. In her story “Cell One”, Chimamanda utilizes drastic changes in tone to relay her message of the importance to stand up against injustice, primarily shifting between a condemning tone in the beginning of the story to a morose style of diction towards the end. Chimamanda tells the story of Nnamabia, the narrator’s brother, whom is taken to jail due to his alleged involvement in a violent cult. His growth as a person and shift in attitude throughout the story symbolize the author’s message of the importance of standing up for those who lack a voice, explicitly indicated through Nnamabia’s sacrifice of his safety by standing up for the helpless elderly man with whom he shared a cell. “Nnamabia stopped there and we asked him nothing else. Instead I imagined him raising his voice, calling the policeman a stupid idiot, a spineless coward, a sadist, a bastard, and I imagined the shock of the policemen, the shock of the chief staring openmouthed, the other cell mates stunned at the audacity of the handsome boy from the university” (Chimamanda 17). The sardonic tone of this passage emanates from phrases such as “stupid idiot” and “bastard” when describing the police officer, which represent an ironic sentiment in the violent and serious events occurring in the story. These are primarily words which would generally not be directed towards anyone in a position of power, much less a police officer who regulates one’s safety. However, Chimamanda’s diction serves to demonstrate the bravery and sentiment of Nnamabia. This represents a shift from the condemning attitude the narrator expressed towards her brother’s actions towards the beginning of the chapter, where she describes him as a “thieving boy” (Chimamanda 7), shifting the passage in a sullen direction subsequent to his imprisonment. This message fits into the overlaying theme of Chimamanda’s stories, in which she suggests the importance of people overcoming the barrier that separates them by their ethnicities, gender, or age and of demonstrating compassion and acceptance towards one another. In this specific story, Chimamanda emphasizes the importance of standing up for others, a universal message she incorporates in her work.

“Arrangers of Marriage” explores the subject of cultural assimilation. In a time period when immigration and ethnic blending is more prominent than ever, Chimamanda discusses the struggles and experiences immigrants (in this piece primarily Nigerian immigrants) have to face in order to integrate themselves to American culture and society. In the story, Chinaza is pressured into an arranged marriage, which gives off the impression of perfection and closely fits in to the ideals of the “American Dream”, yet turns out to be distressing and vexatious. Throughout the story, several motifs representing assimilation are placed, depicted by Chinaza’s relationship with food, her name, and her language customs. From the beginning of the story, the author lays out a conflict in the way Chinaza’s husband eats, and the restrictions he has upon her diet. Chinaza’s husband believes that if she continues to eat her ethnic Nigerian foods instead of adapting to an American diet, she will never be able to adjust to America. Chinaza continuously describes American eating customs as “humiliating” and “lacking in dignity” (Chimamanda 108). When she attempts to cook Nigerian food, she is scolded by her husband because he is “offended” by the smells, and given a cookbook full of American recipes. By embedding symbolism into distinct types of American food, the author suggests Chinaza’s struggle in America, as she does not want to leave her culture behind. This sends a powerful underlying message that it is important to always carry one’s identity with pride, and enforces the belief that a person’s culture is essential to their being. In conflict with these beliefs, Chinaza’s husband continuously makes remarks suggesting immigrants need to completely adopt American culture and leave behind their roots, stating they must “adapt to America. They will never move forward unless they adapt to America” (Chimamanda 108). His continuous push to completely white-wash Chinaza is exacerbated even further by his demand for her to change her name to “Agatha Bell”, because it was “more American”. This pattern of a foreign character changing their name in order to assimilate into American culture is incorporated several times throughout the book, and also demonstrated by Chinaza’s husband changing his name from Ofodile to Dave. Lastly, Chinaza’s wish to attend university, which is denied and overridden by her assigned role as a housewife, represents another major theme in the book with regards to gender roles and barriers in society.

The last major theme incorporated in “The Thing Around Your Neck” highlights the sexism and racism embedded into our society that Chimamanda encourages the reader to resist. She is possibly highlighting the concept of “double jeopardy” as well, which is a historical term first brought to light by Sojourner Truth depicting the reality that black women are one of the most opressed groups in the United States, being forced to deal with both gender restrictions and racial discrimination. To convey her message, Chimamanda tells the story “Jumping Monkey Hill”, which converges the story of Ujunwa, who is attending a writers’ conference, and her fictional story written at the workshop, which consists of a woman who struggles to find a job and is experiencing sexual abuse in the workplace. Through her metafictional piece, the author reinforces the importance of these messages and highlights that despite society’s awareness of these problems, we often ignore them. In the story, Edward, the leader of the workshop, continuously sexualizes Ujunwa, making offensive comments about her ethnicity as well as her appearance. He views Ujunwa as “a fancy without respect,” (Chimamanda 109), suggesting that in Edward’s eyes, her gender and race make her unworthy of humanization and dignity. The author utilizes this sort of demeaning language in hopes that the reader will analyze its cruelty and diminishing nature and take action to stop it. The story is later followed by usage of a rhetorical question, with the author stating “Why do we always say nothing?” (Chimamanda 116). This rhetorical strategy helps the author communicates to the reader that it is our duty to not only stand up for those around us, but to stand up for ourselves as well. She suggests that often, others can make us feel powerless due to ethnic factors or gender, which cannot be controlled, and if people remain quiet, the issue will never meet its end. In order to further amplify her stance, Chimamanda follows with the story “Tomorrow is Too Far,” which depicts the story of a girl who is overshadowed by her brother Nonso because she is female, and therefore loved less than her male counterpart. The narrator is not given a name, which is significant in its stance that she wasn’t considered important enough to even be recognized. In this story, the tree which Nonso falls out of serves as symbolism for power. The narrator’s desire to climb the tree and reach the top before Nonso does demonstrates how she craves the power he possesses, yet her gender is holding her back from receiving it. Nonso’s fall from the tree represents the narrator’s subliminal desire to lessen Nonso’s power, even if her intentions were drafted in a much less drastic way. Chimamanda is successful in telling the story in a way that allows the reader to sympathize with the narrator by exhibiting her lack of power and care in her family relationships. Through the author’s incorporation of phrases such as “Nonso was the only one capable of being a reason, as though you were not in the running” (Chimamanda 138), Chimamanda sets up a clear undermining tone to highlight the narrator’s lack of importance. This provokes the reader with feelings to fight this injustice and as encouraged in her previous works, stand up against it.

The Thing Around Your Neck possesses motifs throughout its stories, communicating the author’s opinions and intentions upon the themes of enduring political persecution, the cultural clash immigrants undergo when arriving in the United States, and the importance to oppose and rebel against sexism and racism in our daily lives. Through her literary style, each story brings a sense of passion and sympathy for its protagonist, and exudes the reader’s duty in correcting this issue. The author suggests that where there is love, there is hope, but we have to constantly make an effort to bring forth those values. As quoted in her essay Why We Should All Be Feminists, “we must do better. All of us, women and men, must do better.”

Illustrations

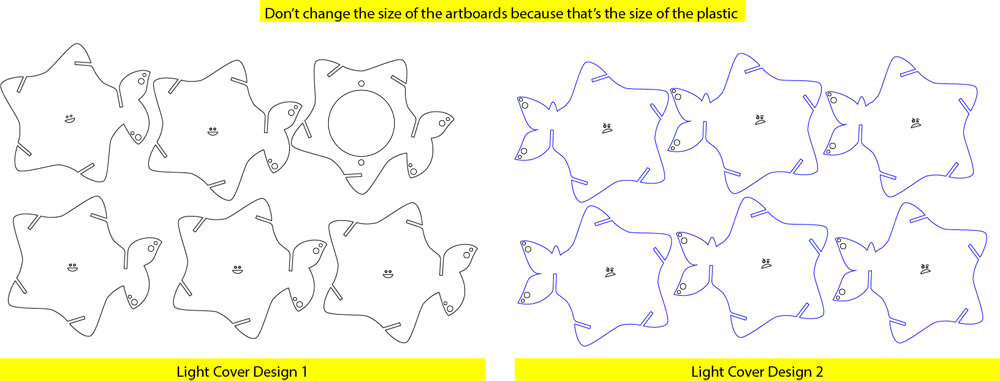

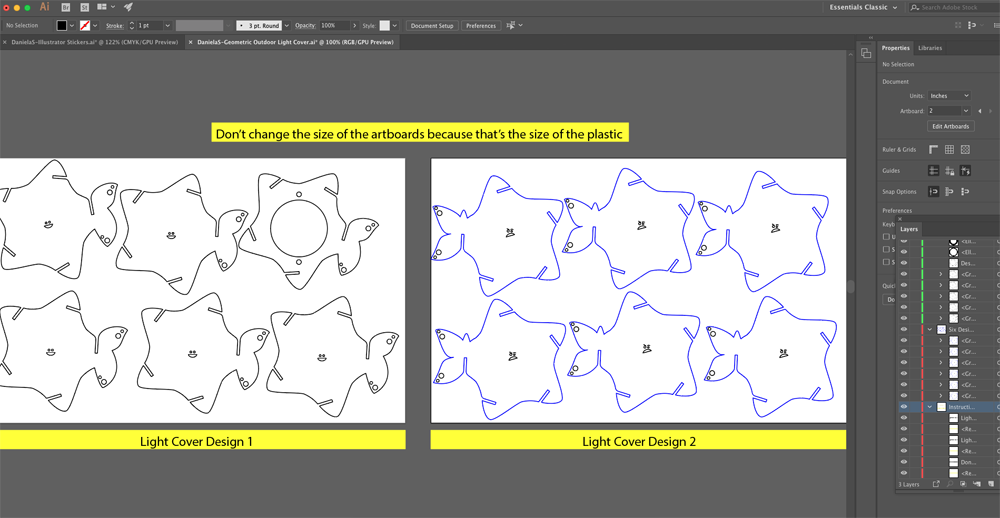

Geometric Light Cover

The Hidden Aspect of Happiness

Through the contrasting components of my geometric light cover, I am attempting to disprove the common misconception that happiness should be the final goal in our lives. It is often thought that happiness is a destination, and that we should constantly be striving to get to that state of mind. However, I believe that emotions are not black and white, but rather a complex scale of greys, and that happiness cannot be achieved without its balancing force of pain and frustration. Through exposing contrasting emotions in my geometric light cover and attaching them together, I am displaying the various sides that happiness entails. The brightly optimistic orange “happy face” is attached to the rather solemn navy “frowny face” to demonstrate that neither of these could be achieved without the other.

Through creating my geometric light cover in illustrator, I bettered my knowledge of the pen tool, particularly when working with fine lines in small spaces. In this specific project, the stroke of the pen had to be especially thin so that the laser would cut the right pieces out. Once my cutout was implemented into the plastic pieces, I experimented, struggled- and eventually got the hang of putting my physical piece together. I wanted to create a simplistic yet meaningful piece of conceptual art that was able to represent a universal message.

Behind The Scenes…

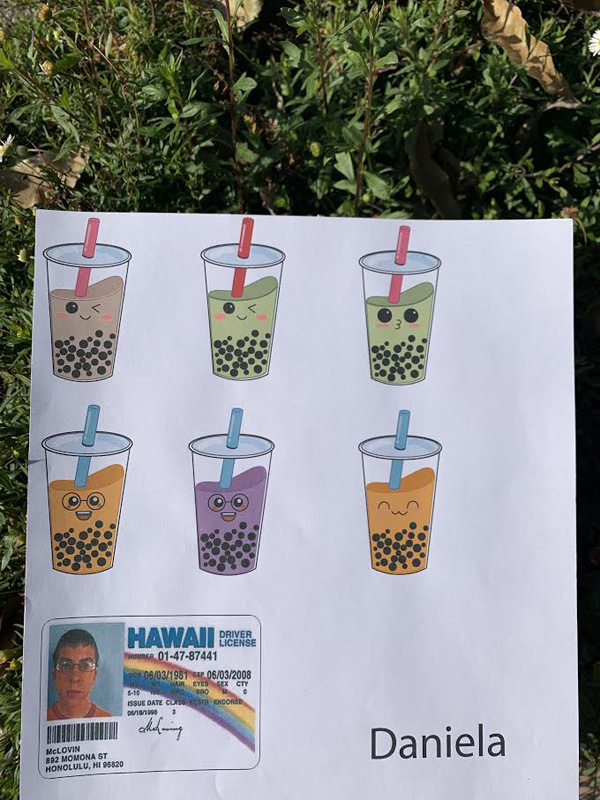

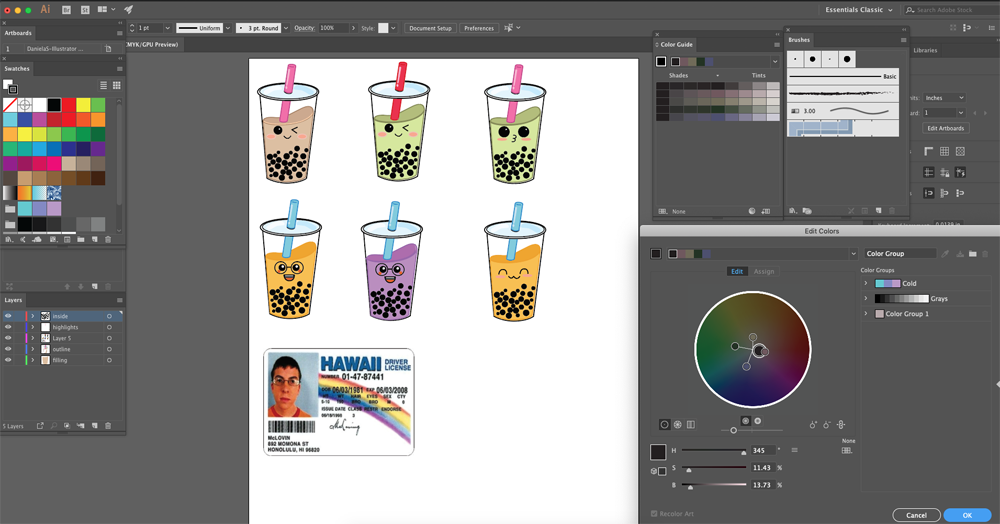

Illustrator Stickers

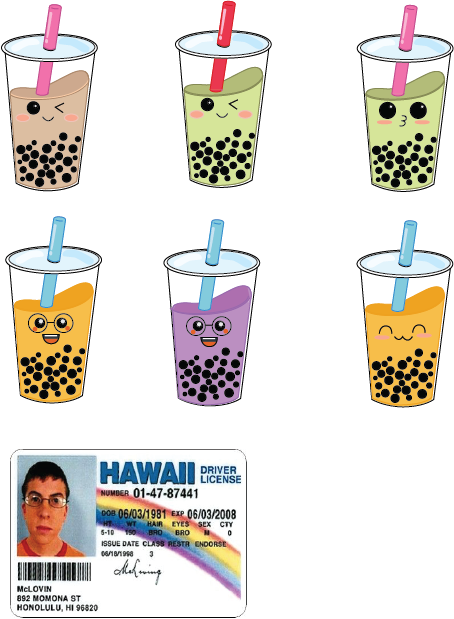

For this digital media project, we were given a wide range of choices to create, from laser engravings to patchwork. With absolute freedom on the content, I decided to make boba tea stickers!

The Boba Craze

As someone who is obsessed- and slightly addicted- to boba tea (or what some people wrongly call “pearl milk tea” or “bubble tea”) it only seemed fitting for me to create cartoon boba stickers. I have always wanted a physical object or decoration to represent my love for this drink, but I had never found any product that I felt was worth purchasing. So, using my knowledge of illustrator, I decided to make my own boba tea stickers. I made several flavors: matcha, black milk tea, Thai tea, and strawberry milk tea (a popular option which I strongly dislike, but the colors were physically attractive). I wanted to add some personality to each drink to demonstrate that no two teas are ever the same, even if they come from the same shop, so I drew distinct facial expressions on each drink. In addition to making boba cartoons, I added the ID from the movie Superbad, simply because I find that aspect of the movie humorous and I thought it would be cool to have on a sticker.

I really valued the freedom that was awarded to us through this project. We were given a wide range of options: from t-shirt designs and phone engraving to wooden plaques and night lights, there was a wide variety of choices to match everyone’s interests. Because we had so much freedom not only in choosing which project to do, but what to do it on, I was able to create something that I particularly enjoyed, which was boba tea! The project also helped improve my Adobe Illustrator skills, particularly working with gradients and clear appearances. Overall, this project was so much fun!

Behind The Scenes…

Design Productions

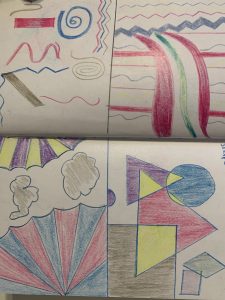

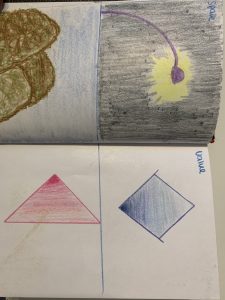

Tints, Tones, and Shades

In order to improve our understanding of the elements of design and tints, tones, and shades, we crafted examples of each using colored pencils. At first, I had trouble grasping the concept and had to redo the assignment, but after reviewing the principles and doing the work carefully I understood.

Narrative Illustration

For our Narrative Project, we created a creature based off of our English short story that showcased the protagonist’s personal traits through a combination of different animals in the appropriate setting. This project is by far one of the most work extensive ones we have been assigned so far. It took many weeks and lots of trial and error. I particularly struggled with working on my project since the illustrator file was overloaded and worked extremely slow- forcing me to work in outline mode. However, this project taught me patience and resilience and greatly improved my graphic design skills.

My story One Last “I Love You” showcases a Guatemalan mother’s journey into the United States along with her two children. In this heartbreaking tale, the unnamed main character, who is running away from her hometown to escape drug warfare and an abusive husband, displays all the difficulties-both mentally and physically, that attempting to cross into the United States holds for immigrants. In this particular scene, the mother has reached the border wall in Tijuana where she is found by border patrol, and faces the difficult decision of leaving her children to cross the border alone, or fleeing back together. Ultimately, she makes the choice to leave her children, knowing they will have a better life in the United States than she could ever give them.

To create this project, I worked with Adobe Illustrator, utilizing features such as grain, texturizers, free-hand painting, gradients, and primarily the pen tool. Through a complex layer structure, I was able to create this creature with attention to detail. My creature is composed of six different animals, each representing a vital trait to the main character of my story. It’s mouth is a duck bill to showcase her motherly instinct, its body is a shark’s to demonstrate her fierceness and resilient attitude (made with gradient and highlight tools), it has a lion mane to represent her fortitude and bravery, a lizard tail to represent her ability to think on her feet, and the face of an owl to show her intense focus and determination on what she deems important. Finally, I added bee wings, utilizing pattern and low opacity, which constitute of the character’s ability to withstand hard work. All of these features combined create a fierce and accurate representation of my story’s character. With regards to the background, I made a long border wall tainted with graffiti and political illustrations (to make my work accurate, I researched current political art). The background was the most difficult part to create because the shape of the wall made it difficult to execute one point perspective, and to create the texture of the ground proved to be a challenge. Overall, I am happy with my project, it is detailed and well executed.