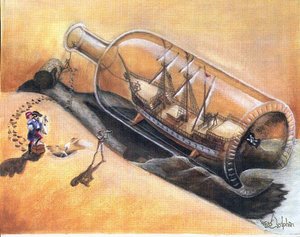

The idea of this illustration was to tell a story with a single image using Adobe Illustrator. My piece was called "The Castaway."

My illustration is of a ship in a bottle floating in a stormy sea. The ship in a bottle is meant to symbolize the sheer impossibility of attaining “perfection,” and how oftentimes this can lead to a cold, melancholy exterior. It was based on the story I wrote for English about a widower who picked up an obsessive hobby after experiencing the painful loss of his wife. He strove to keep the memory of his wife alive and perfect, constantly Windex-ing and cleaning his prized ship in a bottle. But because he tried so hard to preserve this memory of his wife, he ended up isolating himself from his children and becoming very alone. I went about creating the sky by layering a photo and a painting I did to give the piece a more textured feel in order to illustrate this outer appearance. I have had my own personal struggles with this desire to constantly be perfect and live up to everyone’s expectations, especially when I'm really stressed out with large projects and such. I retreat into my shell and isolate myself from everyone and everything. As a result can see myself in the gloomy atmosphere of this illustration.

Ship in a Bottle

Growing up, I remember that my father’s most prized possession was his ship in a bottle.

He put it on his desk in the office, on a specially carved wooden pedestal that allowed for guests to admire everything from the varnished deck to the neat, square sails.

My father liked to tell people that he had blown the glass bottle himself. I guess it was to show everyone that he was capable of creating something beautiful, something perfect. It also spoke to how dedicated he was. His favorite part of the story was about how difficult it was to get the surface so smooth and evenly-rounded, how tedious it was to grind the sand and soda ash together, and how the furnace room felt like the very pits of hell. My father also built the ship inside of the bottle, carving it from a single piece of solid oak and sanding it until it gleamed in the sunlight. The finishing touch was the main sail that he had sewn from my mother’s wedding dress after she died. The white silk always looked a little out of place on the ship’s mast, but my father had insisted on it, saying that it was a piece of her that guided the ship through rough and stormy seas. My brother and I didn’t try and dispute this. We knew how upset our father would be if we tried to ruin his vision of perfection.

The glass bottle itself was kept spotless, always wiped down twice a day with cleaning fluid and a suede cloth. In fact, my very first memory of his office was the pungent smell of ammonia and fake lemon. And if there was ever a fingerprint, any slight indication of human presence, my father would call for a family meeting and scream at my brother and me until his face was purple and his knuckles white.

It was harder for us when we were younger though. My brother and I just didn’t understand why he was always so sad. We didn’t know why he would yell at us for touching his ship, why he would get all upset when field trip forms needed two signatures, or why he would grow quiet whenever he saw family photos with one member missing. All we knew was that something had changed, and with a sort of childlike ignorance, we tried to let it go, figuring that there was nothing that we could really do or say anyway. Or at least nothing we could do to try and ease his pain.

As a result, we didn’t spend a lot of time together. My father never really was fond of talking in the first place, but after my mother died, he became even more of a recluse. Evenings were spent locked in the office, polishing the glass over and over again until his hands were raw and irritated from the cleaning solution. I think he secretly enjoyed the feel of his rough, calloused palms and peeling skin though, for he would always rub his hands together with a tired little smile as if he were pleased with this result of his work. It was as if his hands were evidence of his dedication to the ship in a bottle. Evidence of how much he cared for it. For in a strange sort of way, it was his child and we weren’t.

But even though he cared deeply for his prized possession, it was an impossibility to keep that ship in a bottle perfect and orderly. Because my father couldn’t reach inside the glass bottle to fix the ship, the sails soon started to unravel and the deck started to splinter, slowly crumbling before his eyes. There was nothing his compulsive hands or meticulous eyes could do to stop the gradual disintegration of his prized ship, the ship in a bottle that he had made all by himself.

Knowing that there was no way to really fix it was probably the most painful thing for my father. So, in vain, he kept trying to somehow counteract the decay. For hours, he would just sit on his twitching hands in the office, anxious to repair the damage, but knowing there was nothing he could do. His rationale was that under his careful watch it couldn’t possibly still rot away. And even late at night, he would still stay upstairs, getting up only to switch on the lone light in his office so that he could continue to just sit there in a pitiful, resigned silence. In a way, I think he was blaming the disrepair on his own shoddy craftsmanship and carelessness, even though he probably knew deep down that it was impossible to maintain the ship forever. It was just that my father had always prided himself in being an industrious and productive man, and it hurt for him to not be able to have a tangible result of his dedication and skill.

So as the ship slowly sunk, so did her captain, for she was no longer perfect and neither was he.

Soon came the day when my father laid in the hospital, in the same ward where my mother had died twenty years before. It was difficult for him to talk after the stroke had paralyzed almost his entire body, so during visiting hours I just sat by his side and read to him. He never really listened to me though; instead he always just stared at the ship in a bottle on the nightstand next to his bed. The first night in the hospital he asked me to move it from his office to the ICU. To remind me of  home, he smiled weakly. To remind me of what I’ve done.

home, he smiled weakly. To remind me of what I’ve done.

My father passed away soon after that. In his sleep, the doctor said. There was no pain. That night, I stayed up until the sun rose over the mountains and the roosters started to crow, for my mind was occupied by other thoughts. Occupied with thoughts of patching up white silk sails and varnishing the deck. Occupied with thoughts of gluing fragments of glass back together again. Occupied with the memory of my father.